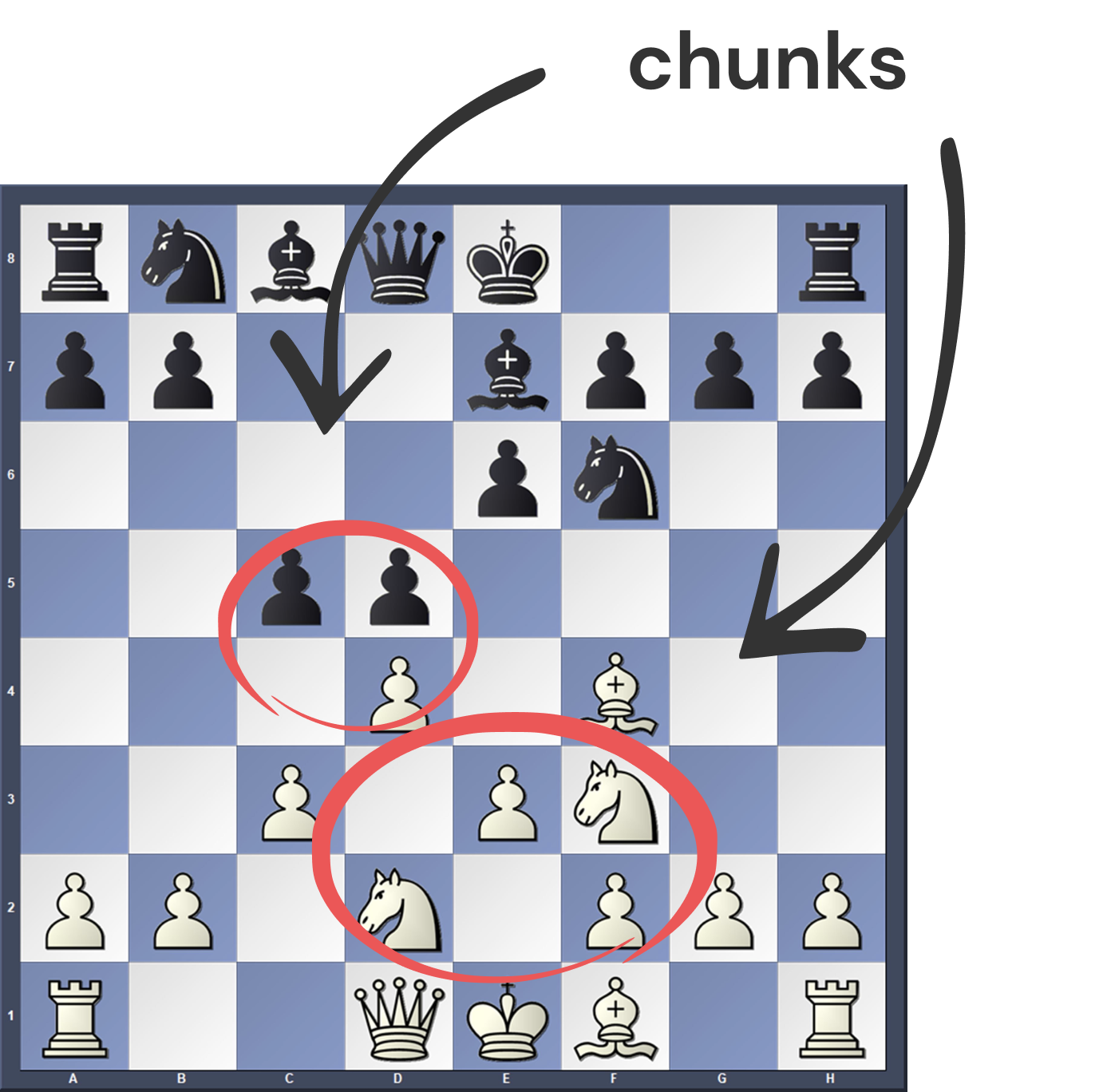

Chunks and templates do not exist as isolated knowledge units. As chess players become more skillful, chunks, templates, and procedures become better organized or indexed and cross-referenced with one another in the course of a learning process that occurs at both the conscious and subconscious level. This knowledge-base enables chess masters to use strategies adaptively and flexibly. With simple problems or high time pressure, masters may rely more on intuition. With complex problems and enough time to think, they will use a combination of intuition and deliberation.20

A chess master’s knowledge-base, therefore, can be characterized as a large set of chunks, templates, and procedures that have been richly indexed and cross-referenced, providing the master with an apparent seamless ability to play better than less skilled players. There is no short-cut to chess mastery. It has been estimated that it may take 10 years or between 3,000 and 23,000 hours of deliberate practice to become a chess master.21